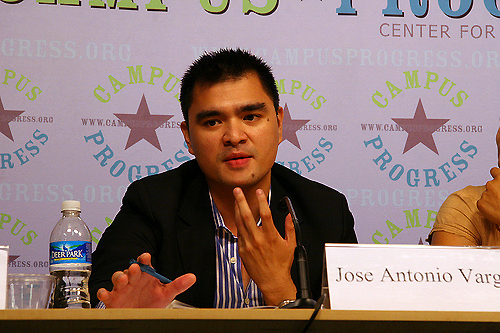

Filipino American reporter Jose Antonio Vargas. (Photo: Campus Progress)

It’s a question I thought was crude and in your face. But if you’re an undocumented immigrant journalist looking for work, there really is no better way to ask – “do you sponsor?”

I’ve been asked this question on occasion in the six years that I was managing editor of a major Filipino American newspaper. It’s a question I always found awkward dealing with. How do you say ‘sorry’ to a friend who calls with the question. The feeling is not any easier when a stranger is the one asking.

I read Pulitzer Award winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas’s New York Times essay, where he confessed to being an undocumented immigrant. I wondered if he ever uttered that question to any of his prospective editors. I’ve been told, it takes enormous guts and a thick face to ask it. Nakakahiya (‘It’s embarrassing’).

From his recollection, it appeared Vargas was able to manage his legal issue pretty well by using a driver’s license secured from Oregon, and a “doctored” Social Security card where the ‘I.N.S. authorization’ text was covered with white tape and later photocopied. Vargas managed to remain subterranean using these two pieces of documentation plus the regularity of checking the citizenship box on numerous official forms. He also filed taxes regularly. He passed for an American citizen.

Vargas was able to apply for a journalism internship with The Philadelphia Daily News in the summer of 2001. An internship with The Seattle Times fell through after he told the company’s recruiter, Pat Foote, about his status.

“After consulting with management, she called me back with the answer I feared: I couldn’t do the internship,” he writes in the essay, My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant. Before that, he worked part-time at The San Francisco Chronicle.

More internship opportunities opened up in 2003 at The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe and The Chicago Tribune, writes Vargas. “But when The Washington Post offered me a spot, I knew where I would go. And this time, I had no intention of acknowledging my ‘problem.’”

The path to the Pulitzer Prize was paved. The talented Vargas was promoted to staff writer after five years, given major assignments, including covering the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings for which the team won a Pulitzer for Breaking News Reporting.

The secret did not remain hidden. Vargas said he came out to the Post’s director of newsroom training and professional development, a guy named Peter Perl. He advised Vargas to stay put, and after he proved himself as a reporter, they would inform the Post’s top management. Did he ask Perl if the Post was willing to sponsor, I wonder.

That discussion never happened because in 2009, Vargas left the Post to join The Huffington Post. Arianna Huffington “recruited me to join her news site,” Vargas writes of yet another step up his career. But the more successful he got, the more he struggled to remain on the down low. The guilt and the pretense were wearing him down.

Vargas’ private struggle is shared by other undocumented Filipino journalists. A reporter I met was willing to move to take on any newspapering job, including mailing and distribution, “if you’re sponsoring,” he told me.

Two reporters working for nonprofit organizations were looking to get married to American citizens. “It’s still the surest way,” one of them said, quoting a lawyer. One was willing to provide her “spouse” a monthly fee until it leads to a green card.

Another reporter, who does part-time caregiving to special-needs adults, won’t even travel outside of his state to come to New York where he has relatives who might be able to help him. He is aware of random racial profiling on trains and public transport, and believes in remaining hidden and undetected.

Some have opted to return to school, where they generally excel and where the welcoming environment of the academe is an exhilarating contrast to a life of frustrating job searches. Financial aid becomes a way to make a little money.

These people admire the courage of Vargas and wish they too could put an end to the lying, the made-up stories, and the anxiety of being found out and put on the next plane to Manila.

But with admiration also comes a certain sense of resignation and resentment. Some of them wished Vargas didn’t have to out himself in such a high-profile way as this might send a red flag to prospective employers who may subject Filipino journalists to more intense scrutiny. Others felt that while the torment of living almost like a fugitive is something they have in common with Vargas, that’s where their shared experience ends. They did not have the same opportunities Vargas had, and do not have his professional credentials.

“He has a Pulitzer; no one deports a Pulitzer winner,” said one.

Cristina DC Pastor is founder and editor of The FilAm, an online magazine for Filipino Americans in New York

AboutCristina DC Pastor

Cristina DC Pastor, a former Fi2W Business and Economics Reporting fellow, is the publisher and editor of The FilAm (TheFilAm.net). Her book, “Scratch the News: Filipino Americans in Our Midst” (Inkwater, 2005), is a celebration of ordinary citizens at the center of extraordinary stories. She is a graduate of The New School.

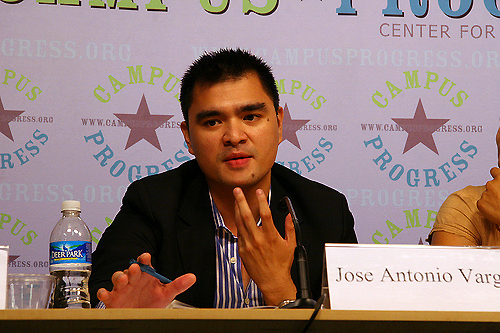

Filipino American reporter Jose Antonio Vargas. (Photo: Campus Progress)

It’s a question I thought was crude and in your face. But if you’re an undocumented immigrant journalist looking for work, there really is no better way to ask – “do you sponsor?”

I’ve been asked this question on occasion in the six years that I was managing editor of a major Filipino American newspaper. It’s a question I always found awkward dealing with. How do you say ‘sorry’ to a friend who calls with the question. The feeling is not any easier when a stranger is the one asking.

I read Pulitzer Award winning journalist Jose Antonio Vargas’s New York Times essay, where he confessed to being an undocumented immigrant. I wondered if he ever uttered that question to any of his prospective editors. I’ve been told, it takes enormous guts and a thick face to ask it. Nakakahiya (‘It’s embarrassing’).

From his recollection, it appeared Vargas was able to manage his legal issue pretty well by using a driver’s license secured from Oregon, and a “doctored” Social Security card where the ‘I.N.S. authorization’ text was covered with white tape and later photocopied. Vargas managed to remain subterranean using these two pieces of documentation plus the regularity of checking the citizenship box on numerous official forms. He also filed taxes regularly. He passed for an American citizen.

Vargas was able to apply for a journalism internship with The Philadelphia Daily News in the summer of 2001. An internship with The Seattle Times fell through after he told the company’s recruiter, Pat Foote, about his status.

“After consulting with management, she called me back with the answer I feared: I couldn’t do the internship,” he writes in the essay, My Life as an Undocumented Immigrant. Before that, he worked part-time at The San Francisco Chronicle.

More internship opportunities opened up in 2003 at The Wall Street Journal, The Boston Globe and The Chicago Tribune, writes Vargas. “But when The Washington Post offered me a spot, I knew where I would go. And this time, I had no intention of acknowledging my ‘problem.’”

The path to the Pulitzer Prize was paved. The talented Vargas was promoted to staff writer after five years, given major assignments, including covering the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings for which the team won a Pulitzer for Breaking News Reporting.

The secret did not remain hidden. Vargas said he came out to the Post’s director of newsroom training and professional development, a guy named Peter Perl. He advised Vargas to stay put, and after he proved himself as a reporter, they would inform the Post’s top management. Did he ask Perl if the Post was willing to sponsor, I wonder.

That discussion never happened because in 2009, Vargas left the Post to join The Huffington Post. Arianna Huffington “recruited me to join her news site,” Vargas writes of yet another step up his career. But the more successful he got, the more he struggled to remain on the down low. The guilt and the pretense were wearing him down.

Vargas’ private struggle is shared by other undocumented Filipino journalists. A reporter I met was willing to move to take on any newspapering job, including mailing and distribution, “if you’re sponsoring,” he told me.

Two reporters working for nonprofit organizations were looking to get married to American citizens. “It’s still the surest way,” one of them said, quoting a lawyer. One was willing to provide her “spouse” a monthly fee until it leads to a green card.

Another reporter, who does part-time caregiving to special-needs adults, won’t even travel outside of his state to come to New York where he has relatives who might be able to help him. He is aware of random racial profiling on trains and public transport, and believes in remaining hidden and undetected.

Some have opted to return to school, where they generally excel and where the welcoming environment of the academe is an exhilarating contrast to a life of frustrating job searches. Financial aid becomes a way to make a little money.

These people admire the courage of Vargas and wish they too could put an end to the lying, the made-up stories, and the anxiety of being found out and put on the next plane to Manila.

But with admiration also comes a certain sense of resignation and resentment. Some of them wished Vargas didn’t have to out himself in such a high-profile way as this might send a red flag to prospective employers who may subject Filipino journalists to more intense scrutiny. Others felt that while the torment of living almost like a fugitive is something they have in common with Vargas, that’s where their shared experience ends. They did not have the same opportunities Vargas had, and do not have his professional credentials.

“He has a Pulitzer; no one deports a Pulitzer winner,” said one.

Cristina DC Pastor is founder and editor of The FilAm, an online magazine for Filipino Americans in New York

AboutCristina DC Pastor