Listen to Ramaa Reddy Raghavan discuss this story on the Feet in Two Worlds podcast:

It is noon and the students at Manhattan International High School stride slowly after lunch into Room 417 for their English Language Learner class. Their teacher Rodica Tenenbaum patiently waits for all the stragglers. Just before shutting the door, 16-year-old Julio Jaime, a smartly dressed teenager wearing hipster jeans and diamond studded earrings, ambles in and sits with his friends in one corner of the classroom.

“Julio, you are not sitting there. Thank you,” says Tanenbaum emphatically, moving him to the center of the classroom.

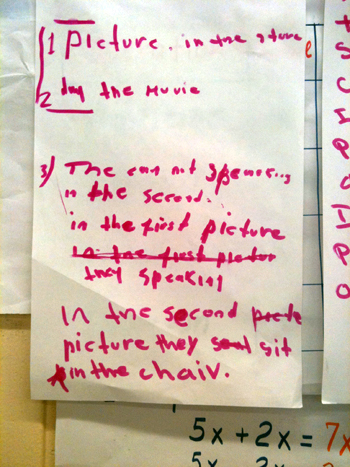

The lesson is about writing topic sentences and structuring paragraphs. Each table is given a large sheet of paper and a marker. Julio, who has a star insignia razored into the left side of his clean shaven head while the rest is gelled, is asked to notate differences between two pictures from a workbook.

He looks around, seemingly lost and does not write a word until Tanenbaum approaches and speaks to him in Spanish. Slowly, with the help of an African girl and two Chinese students he jots down three sparse and illegible sentences.

Like other students at the school, Julio, a 9th grader who immigrated from Ecuador two years ago, has trouble speaking English. But unlike others, he also has a serious attendance problem. As of May of this year, Julio had been absent a staggering 54 days and late 42 days, out of the annual 166 school days.

Julio and other students with a variety of behavioral and emotional problems pose a challenge for the school – should they hire counselors who can help these students, or should they use their limited resources to pay for more classroom teachers? School officials say they can’t afford to do both.

Manhattan International High School is part of the Julia Richman Educational Campus, located at 317 East 67th. The students come from 60 countries and speak 41 different languages. More than a third of them are Latino. The school offers a 9th-12th grade education to students who have lived in the U.S. for four years or less and whose native language is not English.

But language challenges are just the tip of the iceberg for many of these students whose lives become disrupted when dropped into a new culture and style of education.

After repeated phone calls to Julio’s home and a visit from an attendance counselor, the assistant principal Gladys Rodriguez called Julio and his parents in for an interview where she spelled out the importance of school attendance. “Julio’s mother did not say a word but his step-father kept talking the whole time,” said Rodriguez. “I said to the mother, ‘Julio’s like you, very shy,’ and she just smiled. I think the family is aware of the problem but they have other priorities.”

They ended the meeting with Rodriguez drawing up a contract that concentrated on areas where Julio needed improvement which included attending tutoring sessions twice a week. “He verbalized back all the things he had to do to improve,” said Rodriguez, happy with the result. But two days later Julio was absent again and Rodriguez is currently at a loss as to what to do next.

Last year, Rodriguez had a few girls exhibiting similar behaviors so she approached Madelin Gonzalez, a Spanish-speaking social worker at the Mount Sinai Student Health Center housed in the same building as the school.

Gonzalez believed the students’ problems were not severe enough to warrant individual therapy, so she structured a weekly ‘Girls Group’ therapy session for the students Rodriguez had flagged at Manhattan International. Some of the discussions were related to cultural adjustment, anger management, eating disorders, domestic violence and depression.

Rodriguez strongly believes that boys, especially students like Julio, could benefit immensely from weekly group therapy sessions with a Spanish-speaking social worker. She was hoping to start a ‘Young Men’s’ group’ this year with Julio as one of the attendees, but Mount Sinai discontinued the group therapy sessions at Manhattan International. Mt. Sinai declined to comment to Fi2W on the reasons for the cancellation.

This year there was no girl’s group and no hope for a young men’s group. And according to Rodriguez, there aren’t enough mental health services at Manhattan International to meet the demand.

“Last year with budget cuts we lost one guidance counselor,” said Rodriguez. “The one remaining guidance counselor we have spends all her time and energy on the college application process.”

The Department of Education press office said in an email that they have 123 school-based health centers in schools. Of these, seven are affiliated with Mount Sinai. Gonzalez is still working at Julia Richman Educational Campus, but her time is limited to one-on-one therapy for students with serious emotional problems.

One of the attendees that Rodriguez says benefited personally and academically from the girls group last year was fifteen-year-old Winnie Morales, who is originally from the Dominican Republic.

When Morales heard that she had to repeat 9th grade because of her lack of English proficiency, she was livid. But Gonzalez helped her understand that learning English was a necessity for future success and repeating a grade would help her become more proficient in English.

“It makes me feel at peace with myself cause it’s horrible when one tells you to repeat the year,” said Morales. “Cause in my country never repeat a year like here. New country, new language, repeat a year, it was so horrible.”

Like Morales, Julio is considered a ‘borderline case,’ not one involving serious emotional issues, and Rodriguez has been reluctant to send Julio for one-on-one sessions as she has other students facing serious crises who require these resources.

“He’s not truly disconnected as he does engage with you,” said Rodriguez. “But there are deeper issues. The mother does not speak and he does not know how to sort it out himself.” Rodriguez believes group therapy could uncover Julio’s fears and insecurities and alleviate his attendance problem

The administration’s current dilemma is whether or not to use the school’s budget to pay for an additional social worker, at the expense of increasing class size, which could mean less individual classroom attention for students. The current average class size is 24.

“We need to concentrate our resources on having better teachers that can help our student body, which has many English Language Learners with low literacy levels,” said Rodriquez.

Both Rodriguez and Manhattan International’s principal, Alan Krull have had to take on additional responsibilities because of budget cuts. Krull is clear that his priorities lie in providing good instruction for his students.

“We are bare bones right now,” says Krull. “With the budget cuts I lost two para-professionals that speak Spanish and Polish. The last thing I want to cut is special teachers.”

But good classroom instruction seems insufficient to help the needs of Julio and some other students at Manhattan International. Because their families are new to the U.S. and still in transition, problems can be multifold. Even if they aren’t deemed “serious” enough for one-on-one therapy, students are often overwhelmed. Lily Brito, 16, from the Dominican Republic, says she misses hearing what her peers were going through at girls group therapy because it made her feel less isolated. “That it was not just you who had this type of problems,” she said.

“We all come from different parts of the world, we all come with different problems, and really big ones that I didn’t realize. I just looked at my friends and I just didn’t thought (sic) that they were going to have this type of problems, and when they told me I was just so shocked,” she added.

Since he will not be passing 9th grade this year, Rodriguez is concerned that Julio may run out of time to graduate.

“He will be 17 this year and has passed only 8 credits out of 27,” says Rodriguez. “His GPA is at an F so he is over-age and under-credited.

In May she invited Julio and some other students to attend a fair organized with the guidance counselor that discussed alternative methods to receive a high school diploma. These included transferring to easier and more flexible schools. But Julio did not show up.

“Obviously (Manhattan International is) very difficult for him,” says Rodriguez. “We just hope and keep working at it, that’s all we can do. He might be fine next year. But right now I have to call his father and tell him he’s absent.”

Ramaa Reddy Raghavan is a Feet in Two Worlds education reporting fellow. Her work, and the work of other Fi2W fellows, is supported by the New York Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation with additional support from the Mertz Gilmore Foundation.