In early February, when candidates for this year’s New York City Council election were just lining up at the starting gate, Wai Yee Chan, a candidate for District 43 in Brooklyn, sent an email to the two contenders she expected to face in the Democratic Party primary in June. She implored them not to accept a Republican endorsement or nomination if they lost in an area where most voters are Democrats, and the winner of the Democratic primary almost always wins the general election. “A hypocritical bid to further your own political career will do irreparable harm to our collective effort in turning the tide in Southern Brooklyn away from dangerous and extreme Republicans,” the email declared.

The candidates on the receiving end of the email, Susan Zhuang and Stanley Ng, brushed it off as a campaign trick. Zhuang denied having reached out to the Republicans and declined to make such a pledge. Ng stated he is a lifelong Democrat and declined to answer questions about seeking support from Republicans.

But that hasn’t extinguished Chan’s concerns that the historical opportunity to represent this newly drawn Asian majority district might fall to a Republican candidate. “Anything is possible,” Chan said, pointing to the surprise victory of Republican Lester Chang in his New York State Assembly race in 2022.

The City Council district Chan is running in, including Bensonhurst and part of Sunset Park, was created in last year’s redistricting to better reflect the demographics of the neighborhood. Asians make up 54% of the population in the district, and a significant segment is Chinese. It partially overlaps with New York Assembly District 49, where Chang, a Republican Navy Reserve veteran with little experience in politics, shocked New York’s political world last year by beating Democrat Peter Abbate, Jr. who had represented the district for more than three decades.

Nationwide, Asian voters have supported Democratic presidential candidates since 2000. All three Chinese American members of Congress are Democrats. The only other Republican among eight Chinese Americans previously elected in New York was Peter Koo, who, in 2010, became a Council member representing District 20 in Flushing, the city’s only other Asian-majority district. But that was an oddity in a different political climate when the words “red wave” hadn’t flashed in the wildest dreams of Republicans in this traditionally blue city. Koo switched to the Democratic Party not long after he was elected. Term limits led to his departure at the end of 2021.

Wai Yee Chan, candidate for City Council district 43, at a fundraising event in Manhattan Chinatown. Photo credit: Rong Xiaoqing.

Against the backdrop of a political awakening of Chinese voters in recent years and the tendency for an increasing number to vote for the right, Chang’s victory caught greater attention. People along the political spectrum are trying to figure out whether it resulted from a moment of enthusiasm for Republican policies or a sea change in the Chinese community, which has traditionally aligned with Democrats. Part of the answer will come later this year, when all 51 current City Council members face re-election due to redistricting. The new District 43 is the only one without an incumbent.

No one, including Chang himself, denies that his election hinged partly on luck. Having lost two earlier elections in Manhattan’s Chinatown, and well behind Abbate in fundraising and endorsements, Chang did not look like a threat that needed a full-scale pushback from the veteran Democratic incumbent. “He (Abbate) did not take me seriously,“ said Chang. “But what he missed was the message. He did not hear what the people were saying.”

Asian voters make up 58% of Chang’s State Assembly district and a significant number of them are Chinese. The message that he has heard from voters has intensified in recent years, not only in New York, but nationwide. In cities including Boston and San Francisco, Chinese residents, who used to be known as the “silent minority”, have become increasingly vocal in opposing Democrat-backed policies such as legalizing marijuana and allowing transgender students to use school bathrooms based on their chosen gender identity.

More from Immigrants in a Divided Country: On Permanent Resident. Expiration: Never, producer Danya AbdelHameid reports on two immigrant artists exploring the symbolism of the green card and what it means to belong in America.

But it has been education issues that have catapulted many Asian parents—especially immigrants from China—into political activism. A vocal minority of Chinese parents say that affirmative action in college admissions prioritizes Black and Hispanic students. Throughout the country, many Chinese parents also oppose efforts to drop entrance exams at specialized public high schools. Advocates for eliminating exams say it will enhance the diversity of student bodies. But some Chinese parents worry doing so will reduce opportunities for their own children. They have mobilized with unprecedented ferocity to fight back and have succeeded in putting these two issues before the courts and legislatures, even though their views don’t always represent a majority of Chinese voters.

Chinese parents and children protesting in Downtown Manhattan in 2018 against specialized high school reform in New York City. Photo credit: Rong Xiaoqing.

In a survey released last year by AAPI DATA, 69% of Asian American registered voters supported affirmative action and 19% opposed it. Even Chinese voters, the least likely supporters of affirmative action among the six Asian subgroups surveyed, supported it by a margin of more than 2 to 1. Conservative researchers and parents have disputed these results, claiming the survey was worded to boost support.

That argument aside, disgruntled parents now are playing an increasingly critical role in local politics.

Ann Hsu in San Francisco is an entrepreneur, born in Beijing, who until 2021 had never participated in political activities. That year she became concerned that one of her two sons was struggling with online classes during the pandemic. At the same time, she saw that some members of the San Francisco Board of Education were focused on renaming schools named after historical leaders who were now considered racist, as well as repealing the merit-based admission policy of the highly-selective Lowell High School. “I thought we are facing such a big problem [in academic study]. What are you guys doing?” Hsu said.

Hsu and many other Chinese parents who shared her frustration joined the movement to recall three progressive school board members. According to Hsu, they helped register 560 new voters in six weeks to throw out the three board members in early 2022. Then, many of them went on to join the successful movement to recall former San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, whom they deemed to be too soft on crime. Boudin was removed from office in a special election last June.

To Hsu, it is not surprising that more Chinese voters, especially those from mainland China, are leaning to the right. “The politicians on the left have gone too far. They remind us of the Cultural Revolution,” said Hsu, referring to the 10-year havoc ignited by then-Chinese leader Mao Zedong in the late 1960s when millions of intellectuals and those with so-called “rightist tendencies”, including Hsu’s own father, were sent to reeducation camps as the communists sought to elevate the status of workers and peasants. “We immigrants from China all know what the Cultural Revolution was like.”

Growing dissatisfaction with Democratic policies is reflected in exit polls conducted by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund—67% of Asian voters voted for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election and 30% voted for Donald Trump, compared to 79% for Hillary Clinton and 17% for Trump in 2016.

There has been a similar trend in local New York elections in recent years. By the time Chang ran, rising crime and homelessness during the Covid-19 pandemic had already prompted many voters of all backgrounds to think twice about the policies of Democrats who control both the state and the city governments. In the 2021 City Council election, Republicans managed to flip two seats. In last year’s gubernatorial election, the Republican candidate Lee Zeldin, who took public safety as his campaign pillar, lost to Democratic incumbent Kathy Hochul by less than 6 percentage points, the closest New York governor’s race since 1994.

Political activism by members of the Chinese community increased dramatically in 2018 as parents protested New York City’s specialized high school reform plan, proposed by Democratic mayor Bill de Blasio. The plan included the elimination of the admission exam known as SHSAT for the city’s best public schools. Chinese residents went on to organize and participate in rallies against the city’s plan to build homeless shelters and jails in their community, and the state’s cashless bail law that allows some suspects to be released quickly after being arrested.

Chinese parents formed their own rights organizations and political clubs, held voter registration events, and endorsed and campaigned for candidates they deemed to represent Asian values. In the mayoral election in 2021, the Republican candidate Curtis Sliwa, although losing by 40 percentage points citywide, won in many Asian districts by large margins. Those gains were repeated a year later in the gubernatorial election. In Chang’s district, Both Sliwa and Zeldin won more than 60% of the vote.

Lee Zeldin, the Republican candidate in New York’s 2022 gubernatorial election met his Chinese supporters at Sunset Park, Brooklyn. Photo credit: Rong Xiaoqing.

A parent who attended his first public demonstration in 2018 after Mayor de Blasio announced his specialized high school plan, Ling Fei has since become a major conservative activist in the Chinese community. In a blog entry in July, more than three months before the election, Fei predicted Chang’s victory. “I have witnessed the whole process of the political awakening of the Chinese community,” said Fei, who now works part time at Chang’s office as a community liaison. “I knew it was the time.This is a process of quantitative change leading to qualitative change,” he said.

Some Democratic officials seem to be taking note of the changing mood. John Liu wrote an op-ed piece in the Huffington Post in 2012 when he was the city’s Comptroller (and the first Chinese person elected to that post), calling for specialized high school reform. Today, Liu is a fierce defender of the SHSAT as the chairperson of the State Senate’s Committee on New York City Education.

Ari Kagan, who was elected to the Council in 2021 as a Democrat, switched to the Republican Party at the end of last year. Kagan, whose district in southern Brooklyn is 20% Asian, said Asian voters feel Democrats don’t care about public safety, and many of them worry the Democrats are leading the city to socialism. “People from China, from Korea, from Venezuela, from Cuba, from the Soviet Union, they know socialism is terrible. It makes everyone equally poor,” said Kagan who immigrated from Belarus, a former Soviet republic.

After Chang was elected, Democrats controlling the State Assembly considered removing him based on an eligibility requirement in the state constitution concerning a candidate’s residence. Ron Kim, a Democratic assemblyman representing Flushing, told The New York Times that “a lot of Chinese voters feel like this is an effort to take away a Chinese person who was elected by the people in that community.” The idea was eventually dropped. “They knew if they ousted Lester, more Lesters in our community would stand up and run for public offices,” said Phil Wong, a pro-SHSAT parent-turned activist who traveled to the state capital in Albany several times with other Chinese voters to support Chang.

Whether more Lesters will run is what Chang has now set his sights on. “The real test is this year, City Council,” said Chang, adding that if a Republican is able to win in Flushing or the new district in Brooklyn, “that means the change is solid.”

So far, both districts are expected to have a Republican primary, a rare occasion in New York local elections, with at least two Chinese contenders each. Democratic candidates in the districts seem to be taking Chinese voters’ concerns seriously–none of them would identify themselves as “progressive.” “I am not progressive but a moderate. I don’t agree with some progressive ideas,” said Chan, the candidate in District 43 who authored the email.

“I recognized at the very early stage that my constituents, the community, their views are probably not going to be aligned with the progressive caucus stances,” said Sandra Ung, the incumbent council member in Flushing, explaining why she didn’t join the council’s progressive caucus.

But this doesn’t mean Chinese voters are guaranteed allies of Republicans. Nationwide, Republican-led policy proposals like S.B. 147 and S.B. 711 in Texas, which seek to restrain Chinese citizens, among other foreigners, from purchasing property in the state, have triggered strong waves of protests, especially from Asian immigrants and their offspring. At a recent public hearing held by the Texas Senate Committee on State Affairs, more than a hundred Chinese people testified against the bills. Many said the proposed legislation reminded them of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the 1882 law banning Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States.

In New York, at least one district has shown that the Chinese community is not a monolith. Bearing the brunt of anti-Asian hate, residents in Manhattan’s Chinatown have fought the city’s plans to build homeless shelters and an expanded jail in the neighborhood. But the district shows no sign of turning red.

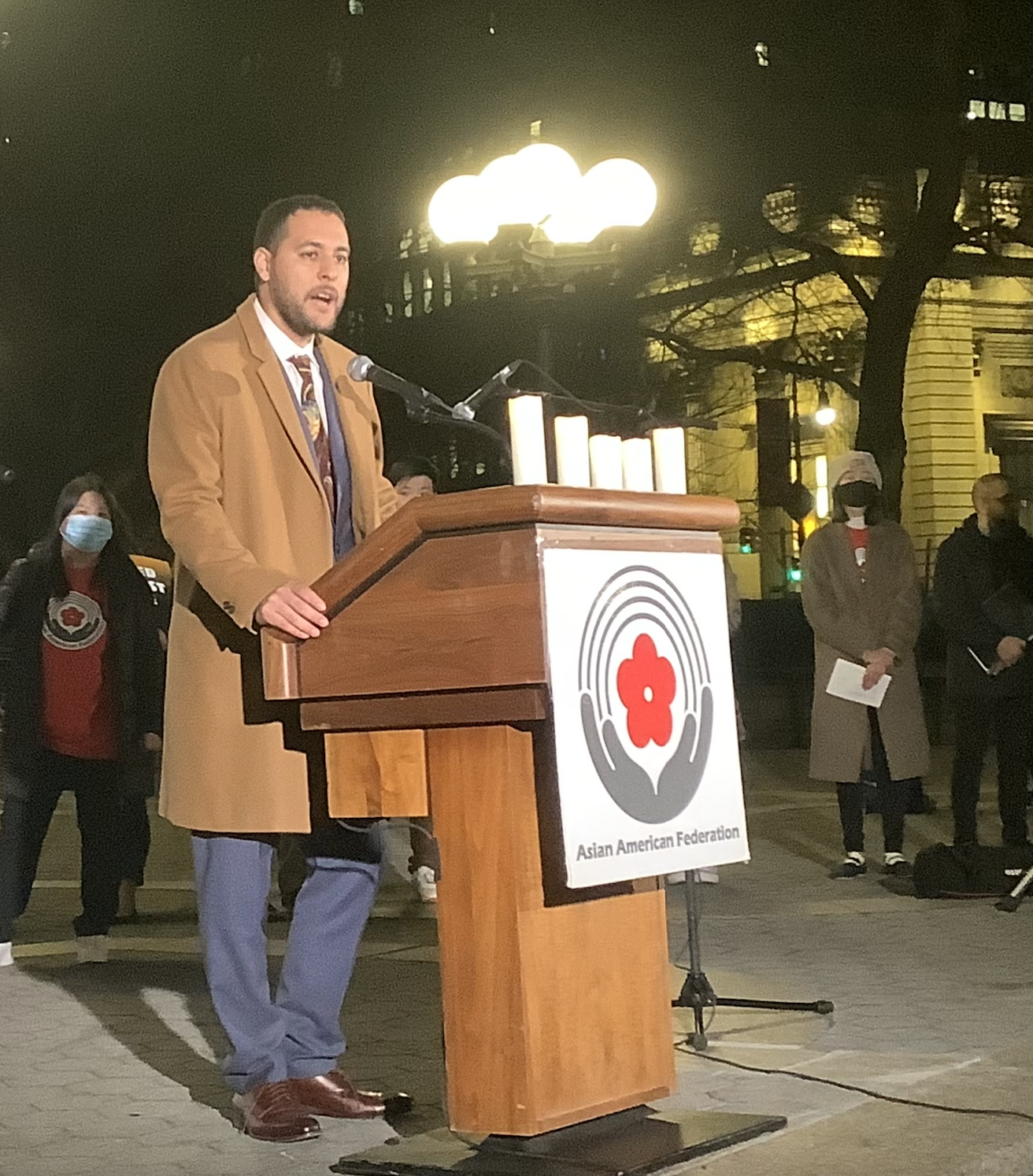

New York City Council member Christopher Marte spoke at a rally in Union Square condemning anti Asian hate. Photo credit: Rong Xiaoqing.

This is also what sets apart Christopher Marte, the council member representing Manhattan Chinatown, from Democratic candidates in New York’s other Chinatowns in Brooklyn and Queens. Marte has been holding high the “progressive” torch since his campaign for City Council in 2021. “I still won the majority of the Asian vote in Lower Manhattan,” Marte said. “While the right might use fear-mongering to agitate people, we have not seen that be effective in Lower Manhattan.”

Neighborhood demographics may help explain the differences between Manhattan’s Chinatown and the city’s other Chinatowns, such as Flushing, Sunset Park, and Bensonhurst. With lower median incomes and rates of homeownership, and a higher percentage of senior residents than those other neighborhoods, Manhattan’s Chinatown may have a greater need for social services and welfare, which are signature causes of the Democratic Party.

This backs up a belief among many community insiders that Chinese voters vote on issues not according to a candidate’s party affiliation. “In South Brooklyn, Chinese voters have no party loyalty. They vote for the candidates who can provide services,” said Iwen Chu, a former chief of staff for Abatte, who was elected state senator last year in the area.

Chu, a Democrat who also refused the “progressive” identity tag, said she is an immigrant whose values cannot be summarized with a single label. She says the same can be said for Chinese voters in general. Chinese immigrants are more likely to be conservative on the economy because they don’t like high taxes. But low income Chinese rely on welfare, which is supported by Democrats. “I hope neither party takes us for granted and overlooks our real needs,” Chu said.

People from both sides of the political aisle seem to agree with that sentiment. Yiatin Chu, a pro-SHSAT parent turned-activist who co-founded the political club Asian Wave Alliance, has supported many Republican candidates. Now, she works part time in the office of Republican assemblyman Chang’ but remains a registered Democrat. She said the views of the Chinese community haven’t changed, whether it is about meritocracy or public safety, but Chinese voters are more aware of candidates’ positions on issues and have a better understanding of how to use their ballots to get the policies they want. “I don’t think it’s us moving. It’s the other way around,” Chu said.

That may mean harder work for politicians, during campaign season and beyond. “Will Chinese voters go right or left from here? It depends on how the two parties will try to win us over,” said Fei, the blogger.

This story was produced in partnership with Sing Tao Daily.

Feet in 2 Worlds is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation, the David and Katherine Moore Family Foundation, the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation, an anonymous donor and readers like you.