Deybeth Ruiz Outside Eloy Detention Center. Photo: Valeria Fernández

Karyna Rodríguez Jaramillo walks past the last blue security door of the Eloy Detention Center on a Saturday morning in April. Her team of volunteers drove for more than an hour to visit detainees who identify as LGBTQ held at the private immigration prison 66 miles outside Phoenix. She is dressed in black tennis shoes, yoga pants and a short-sleeve t-shirt layered over white long sleeves. She’s tall. Her brown dark wavy hair is pulled back in a ponytail that shows a few grey hairs. Her black eyes take a deeper almond shape accentuated with a black line that extends at the edge.

It’s a vulnerable moment because it opens the wounds of the time she was held at Eloy in 2015. As a transgender woman she felt humiliated by the jokes and harassment by detention officers and the men she was incarcerated with.

For us sanctuary really looks like having a space that is safe for LGBT people, it goes far beyond changing immigration laws.”

Karyna Rodriguez Jaramillo; photo: Valeria Fernández

Rodriguez Jaramillo, who is 46, said that back then she didn’t understand the concept of gender identity and knew almost nothing about immigration laws or applying for asylum. Now, she helps detainees and others as the defense coordinator for Trans Queer Pueblo (TQP) – a grassroots non-profit organization in Phoenix led by LGBTQ immigrants and people of color.

For more than a decade LGBTQ immigrants like Rodriguez Jaramillo were among those that bore the brunt of Arizona’s notoriously harsh immigration policies. Now, members of TQP are turning around the narrative that casts them as victims, and they are taking the immigrant rights movement in a new direction. It’s a bold strategy that doesn’t just challenge authorities who enforce immigration laws, but also those who would appear to be Trans Queer Pueblo’s allies, immigrant rights advocates and the mainstream LGBTQ movement.

Read more in our online magazine Is it Safe Here? Redefining Sanctuary in the Trump Era.

The young organization is made up of people like Rodriguez Jaramillo, who live at the intersection of both their LGBTQ identity and being undocumented immigrants– they have experienced detention, discrimination, racial profiling and violence.

Their work takes place at a time when the Trump administration and Republican members of Congress are pushing legislation to punish cities and states that have declared themselves sanctuaries for undocumented immigrants. This is in addition to an executive order signed by the president early in his term to deny federal funding to sanctuary cities.

But the sanctuary policies that are in the crosshairs of President Trump and his allies in Congress are different than the concept of sanctuary advanced by LGBTQ immigrant advocates. As they see it, sanctuary is not something they seek. It is something they create.

“For us sanctuary really looks like having a space that is safe for LGBT people, it goes far beyond changing immigration laws. It has to do with making sure that not only immigrants and LGBT people are protected, but that we’re also talking about the state violence that our black and brown brothers who are citizens also suffer. It’s also talking about economic justice,” said Dagoberto Bailon, the general assistant at TQP and one of the founders of the organization.

“It is far more than a place, it is a system that we want to build where we can exist and be our whole selves,” he said.

“You’re very important to us”

Rodríguez Jaramillo is at the Eloy Detention Center to see a man who asked that his identity be protected because he fears for his life if he is deported. She knows he is from Haiti and that he is seeking asylum. She hopes they’ll be able to communicate.

It’s barely 7:30 a.m. and the waiting room is packed with families. Some toddlers are restless and oblivious to a TV offering cartoons.

After 2 hours of waiting, a detention officer yells the detainee’s name and Rodríguez Jaramillo goes into the visitation room. The place looks like an enclosed cafeteria with tables, vending machines and a microwave to heat the food visitors purchase for detainees.

She spots him from a distance. He’s as tall as her, about 6 feet. He looks eagerly from a distance.

They sit across each other on a table painted with red and blue squares and the inscription: “Solitaire. A game for one.”

“We’re with Trans Queer Pueblo,” she tells him.

“Yes, I know,” he responds in Spanish, covering his face with his hands to conceal a wide smile. He’s 34 years old and speaks with a hint of a Dominican accent.

He’s been in Eloy since the end of January.

“You’re very important to us,” Rodríguez Jaramillo tells the man after listening for a while. Her words sink in for a moment. This is the first time they have met, yet he appears comfortable opening up to her. He tells her that he feels harassed inside the detention center.

“You’ve been in here, you know what it means to have someone visit you,” he says.

But Rodriguez Jaramillo never had anyone come to see her. She knows she can’t break down in front of him. So she holds herself back and shows a smile all the way to her cheekbones.

That’s part of the reason she does this work. Although it took her sometime to realize she was capable of doing it.

After her experience in detention she was depressed and didn’t want to live.

She came knocking on the door of the Arcoiris Liberation Project, a predecessor of TQP, looking for money for her many legal expenses to fight her deportation.

But they didn’t have any, said Dagoberto Bailon.

“I recall she kept coming because it was the first time in her life that someone had respected her pronouns and her names,” said Bailon, a 30-year-old gay undocumented immigrant. “Because from the get-go she was asked, what was her preferred gender pronoun and she was like: ‘I’m a woman. I will always be a woman. I was born a woman’.”

Bailon and others were in the beginning stages of founding TQP and persuaded her to apply for a position. In 2015 they merged the Arcoiris Liberation Project with the Queer Undocumented Immigrant Project to create Trans Queer Pueblo.

Rodriguez Jaramillo who has a high school education felt she was unqualified to apply, “I have no studies,” she told them.

She remembers one of their members countered: “You’re the ultimate expert on this because you went through the process. You went through it. What do you want for others now?”.

It didn’t take long until Rodriguez Jaramillo found her place in the movement and emerged as a leader.

Self-defense

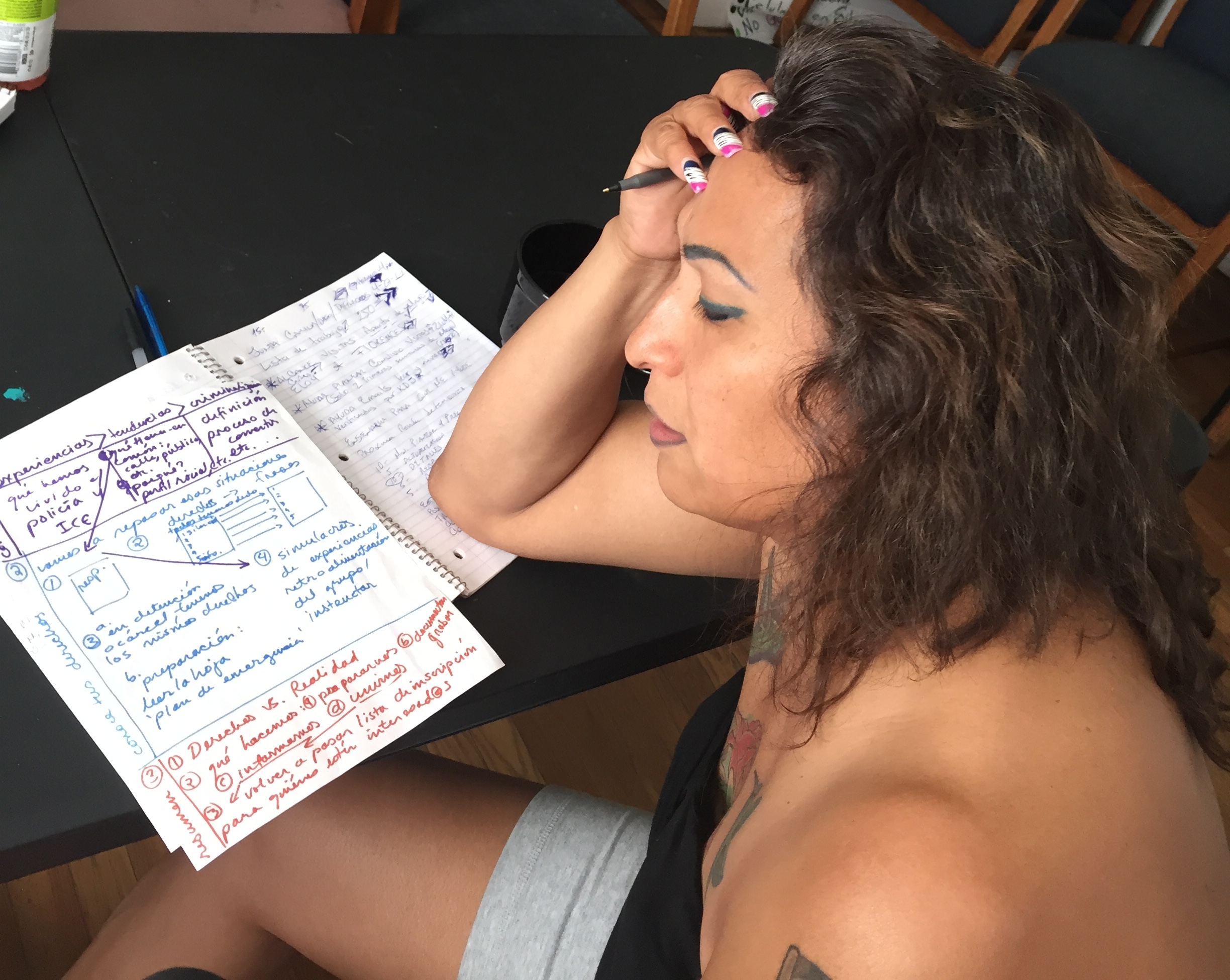

On a warm Sunday afternoon in May, Jaramillo Rodriguez hosts a meeting at Trans Queer Pueblo.

She sits at a table meticulously going over notes on her laptop. She’s wearing a formal pastel colored flower dress that bears one of her shoulders and reveals the beginning of an intricate hummingbird tattoo.

She’s both excited and nervous. It’s only TQP’s second self-defense training, a program she helped design so that others can find a legal way to gain immigration protections in the U.S. That involves them initiating their own immigration cases and representing themselves in immigration court to identify a pathway to adjust their status or gain documentation.

We are trying to flip power dynamics, when LGBTQ people are seen as a resource then people are willing to engage…We’re building and we’re changing the perspectives of people.”

“What is your preferred gender pronoun?” Jaramillo Rodriguez asks each of the three participants.

Deybeth Ruiz, a 36-year-old transgender man joined the training because he was cheated out of his salary for 3 months at a construction site. With legal documents he feels he would be able to assert his rights at another job if he is exploited again.

“The situation here is very difficult, they abuse you [at work], they threaten you so you can’t go work somewhere else and exploit you,” says Ruiz.

All of the participants have to sign a contract. In it they commit to volunteer with TQP and also be a mentor to others.

“Everything in life has some risk, but if we don’t run the risk we won’t know what could happen,” says Rodriguez Jaramillo.

They will be representing themselves legally, but there’s an attorney present to inform each of the participants about different forms of immigration relief that might help them. The attorney explains that asylum is an option for some people, but it needs to be requested within one year of coming to the U.S.

If Jaramillo Rodriguez had known this, her life might be very different now.

She came to the U.S. from Cuernavaca, Mexico when she was 17. After being sexually assaulted several times she asked Mexican authorities to help her. Instead the police labeled her as a prostitute.

In the U.S. her experience wasn’t that different.

“They always referred to me in male terms,” she said, about her interactions with the police. “Why do you dress like that if you’re a man?”

When she was sent to the Eloy Detention Center men would make sexual comments, they even wanted to have sex with her. She became fearful, “that someone would touch me and harm me or abuse me and on top of that make accusations against me.”

But the greatest fear of all was that a judge would rule that she’d have to go back to Mexico.

“That would be like signing my death sentence,” she said.

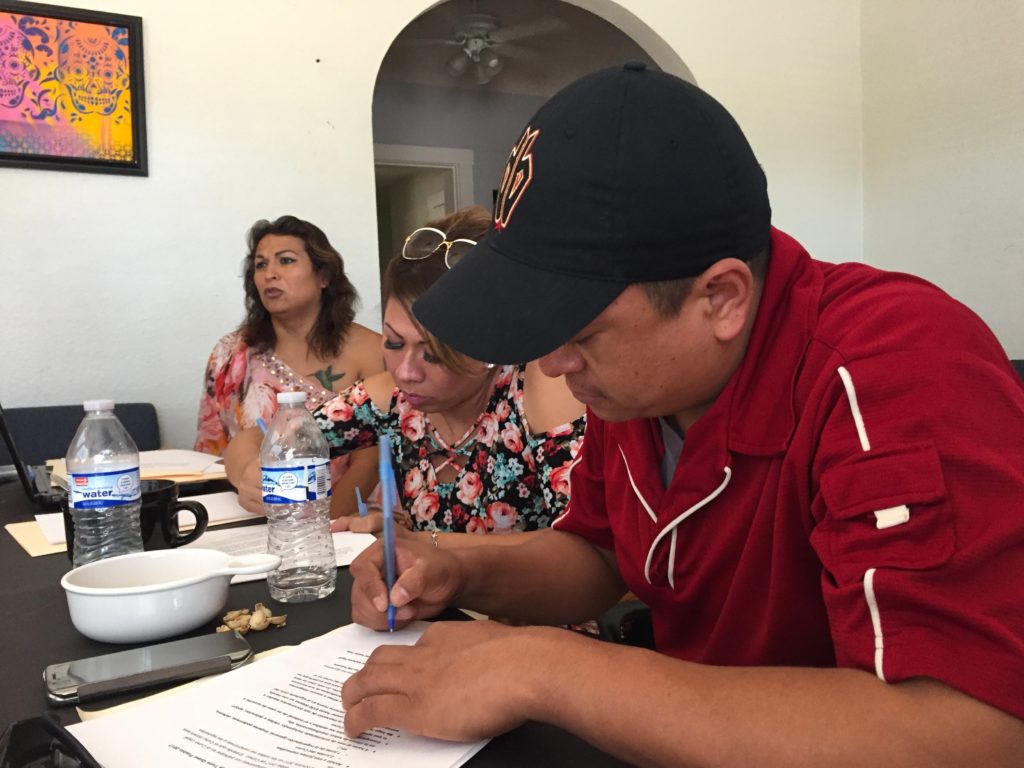

Legal Defense Training at Trans Queer Pueblo. Photo: Valeria Fernández

Changing power dynamics

Trans Queer Pueblo is located in what looks like a typical family house in Central Phoenix. Just a block away is Ranch Market, one of the biggest grocery stores serving the area’s Mexican and Latino communities.

Bertha Fabian, a Mexican immigrant lives a few blocks away and found TQP when they were holding a potluck in their yard.

“We’re living through a lot of discrimination and injustice and our human rights are valuable. Thankfully we have someone helping,” said Fabian in Spanish.

Reaching out to families like hers has been intentional for TQP.

“We are trying to flip power dynamics, when LGBTQ people are seen as a resource, then people are willing to engage,” Bailon said. “We’re building and we’re changing the perspectives of people.”

Fabian recently attended a “Know your Rights” training organized by TQP. The training included what to do if immigration officials come knocking at the door, how to interact with police during a traffic stop, and a review of constitutional protections extended to all people in the U.S regardless of status.

Phoenix is not a sanctuary in the sense of having policies that prevent the police from inquiring about a person’s immigration status. In Maricopa County, the county that encompasses Phoenix, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) plays a more active role in the local jails than they do in many other parts of the country. All persons entering the jail are interviewed by ICE, and the agency is notified when county officials are ready to release someone ICE has already flagged for violating immigration laws.

Across Arizona police officers are required to enforce SB 1070, a state law that makes it mandatory for them to inquire about a person’s immigration status if they suspect they are in the country illegally.

For transgender immigrants and people of color other city policies put them at greater risk of deportation by increasing the likelihood that they will become entangled in the criminal justice system. A Phoenix city code commonly referred to as the “manifestation law” allows police to arrest anyone suspected of prostitution by exhibiting certain behaviors including waving at vehicles.

Francisco Luna, a member at TQP and former coordinator of Joti-PoliticAZ – a pilot project to voice the organization’s political opinions – says it’s “a way to funnel people of color” as well as transwomen and transmen into the local jail where they will come into contact with ICE.

“No justice, No pride”

Much of Trans Queer Pueblo’s work takes place quietly, behind the scenes. But on April 2, they put themselves in the spotlight when they disrupted the route of the annual Phoenix Pride Parade chanting “Sin justicia, no hay orgullo” (No justice, no pride).

Their message was: You can’t celebrate equality when LGBTQ immigrants are targeted by local police, criminalized by state policies and funneled into immigration detention, said Luna. They claim that Pride has become commercialized and has moved away from its roots grounded in protest.

The response to the protest raised alarming questions for some within the mainstream LGBTQ movement about the presence of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment in their midst, said Ray Bradford, the chair of the LGBT Democratic Caucus.

A video of the protest show that some in the crowd tried to physically stop protesters, others got into heated arguments with them. At moments they were booed. Images show police intervened to break up the confrontations, but no one was arrested or got hurt.

A few days earlier TQP had publicly called on Pride to end the participation of LGBTQ police officers in the march, and reject sponsorship from banks with investment ties to corporations that run private immigration detention prisons.

TQP primarily focused on Bank of America, the main sponsor of the parade. The bank finances debt for the GEO Group and CoreCivic, both private corporations that run detention centers across the country. CoreCivic runs the Eloy Detention Center and 5 other prisons in the state.

According to a report by In the Public Interest based on documents from the Securities and Exchange Commission, Bank of America is among the six banks that played a role in financing the debt for these private prison corporations. In an email, Bank of America declined to respond directly to Feet in 2 Worlds’ query regarding their ties to the detention center.

Phoenix Pride and TQP attempted to meet after the parade to discuss their differences. The meeting never happened. But Justin Owens, executive director of Phoenix Pride told Fi2W in a phone interview: “Phoenix Pride is committed to addressing inequality in our community in any way we can.”

Owens explained that because they are a non-profit they have restrictions when it comes to issues of policy or politics.

“We agree that some of their issues are something that very much needs to be addressed,” said Owens.

But Owens also said that allowing the police to march in the parade is about inclusiveness, and their presence there is also required for security reasons by state and city laws.

For members of TQP, the police presence has a very different association. “For brown communities and black communities, the police, it’s a trigger and we have suffered so much violence at the hands of the police and continue to do so. So, saying that the police presence is keeping us safe, I wonder, keeping who safe?” Bailon asked.

Owens also praised Bank of America for having policies that support their LGBTQ employees and for the contributions that extend to the organization’s philanthropic work.

But he added “based on the heightened sense of what’s happening right now, we’re absolutely open to a different way of evaluating our sponsor so everyone feels included.”

Great need, little resources

Trans Queer Pueblo is not alone in their work. There is a growing movement nationwide to better address the needs of immigrants who identify as LGBTQ.

“Trans leaders are feeling this moment of rapid response,” said Isa Noyola, director of programs at the Transgender Law Center, an advocacy organization based in California. “The culture of fear is pushing folks further to seek community, to seek sanctuary, even if it is within a small living room.”

Noyola, a trans Latina said most groups are doing this with very little money.

“They’re doing case management out of their cars, they’re handing out condoms in the clubs, they’re out protesting, they’re feeding communities, they’re thinking about safety strategies, they’re doing all of these things with very little resources,” said Noyola.

Conversations about what sanctuary means and what it takes for a city or town to become a sanctuary are happening at the national level too.

“The idea of sanctuary is that it should not be just site specific, that sanctuary should be embedded into the culture of the community,” said Noyola. “It should be a transformational process in which the ideas and all of the things we’re fighting against: Homophobia, transphobia, racism, xenophobia, all of the things are transformed into positive interventions in a way to restore justice at the moment for those experiencing it and those witnessing it.”

Karyna Rodriguez Jaramillo; photo: Valeria Fernández

While the conversation over the meaning of sanctuary continues, some LGBTQ immigrants recognize they may have to seek sanctuary in a physical space like a church, said Francisco Luna, a member with TQP and former coordinator of Joti-PoliticAZ.

But even if that necessity arises TQP wants to move away from the idea that its members are disempowered and need a “white savior” to offer protection, said Luna.

“The hierarchy structure of a church reminds me too much of how things work inside a detention center where many people have been detained,” he said. “If a member seeks sanctuary we want them to be able to make their own decisions while they’re there, and no one else.”

Rodriguez Jaramillo has her own pending asylum case coming up under an exception in the law for people who are transitioning. While she waits, she keeps busy. By June she was supporting at least 5 detainees from Haiti.

“It’s the hope I didn’t have when I was inside, to have someone to come and visit you and say: “We’re with you,” she said.

Meanwhile she says she finds sanctuary in her daily work.

“I think it’s simple, it’s a house, a home, a space where you can have liberties and rights, where there is equality and there’s not an obligation to tell anyone or to be told how you have to be,” she said.

Read More stories from our magazine, Is It Safe Here? Redefining Sanctuary In The Trump Era.

Fi2W is supported by the David and Katherine Moore Family Foundation, the Ralph E. Odgen Foundation, The J.M. Kaplan Fund, an anonymous donor and readers like you.