The third in a series on the 2010 Census and immigrant communities.

New York – Middays are always busy at the Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, a community center in South Brooklyn. Residents of the area, many of them Russian-speaking immigrants, come here seeking help with all kinds of daily issues. Seniors come for lunch, youths and adults for educational programs or to use sports facilities. But on recent days some also stop by the center’s lobby where a table marked with the census logo stands in a corner. At the Census Questionnaire Assistance Center (QAC), one of approximately 90 such places in South Brooklyn, a census employee is on hand 3 days a week to help people fill out their census forms.

Mira Khabarova, 75, who came to the site on a recent Wednesday, said that for her participating in the census “was a must.”

“It’s important to know how many people live in the neighborhood. Government needs this information to make a plan on how to develop the area,” she said through a translator, adding that she is also aware that submitting the questionnaire may have a potential impact on the number of congressional seats assigned to the area.

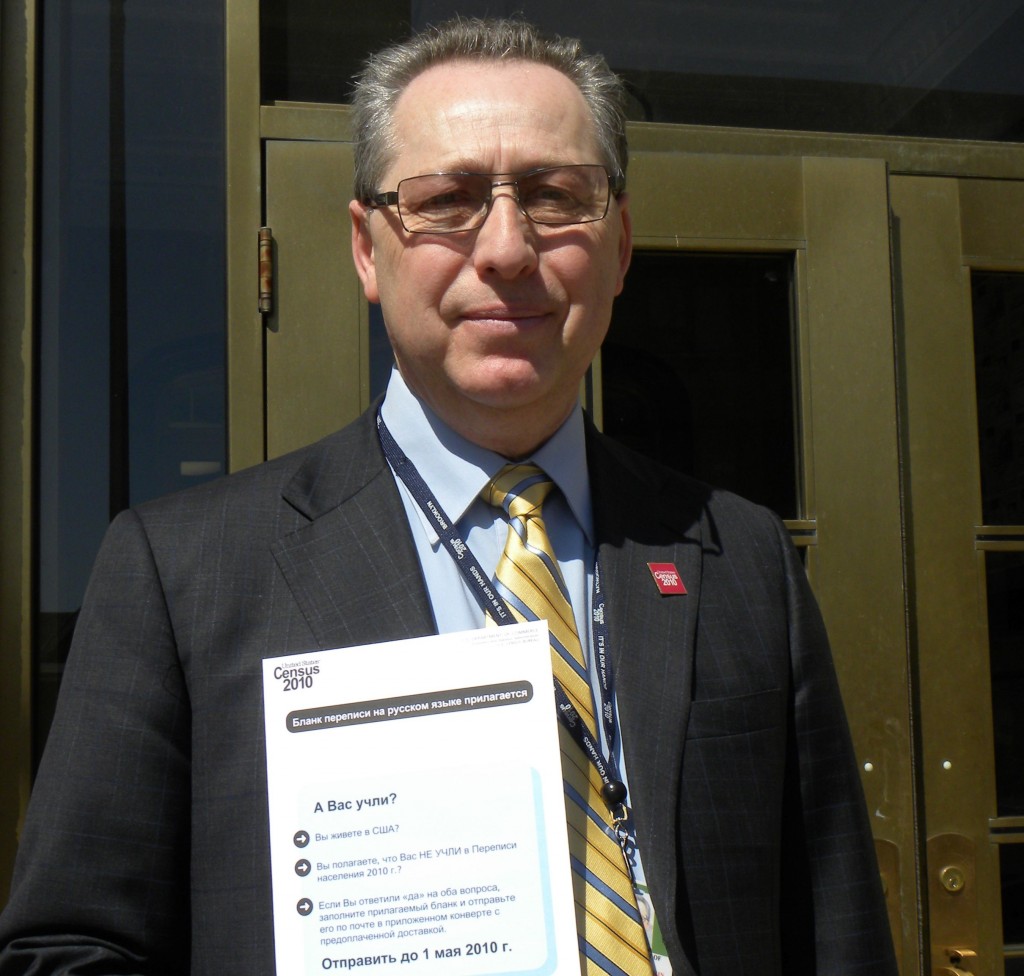

Valeriy Savinkin, US Census Bureau partnership specialist and a Russian community liaison, does not believe that offering the questionnaire in Russian will make a significant difference. (Photo: Ewa Kern-Jedrychowska)

Khabarova, who immigrated to the US from Ukraine, could almost star in a census ad, although this is the first time she is participating in the count during her 17 years in the country. “Last time I didn’t hear about it,,” she said. This year her knowledge about the counts’ purpose and benefits came mostly from Russian-language media which have been distributing information on the census, both through news stories and ads.

But many Russian-speaking immigrants are more skeptical. “They remember the government in their old country and they don’t believe that something may depend on them,” said Valeriy Savinkin, a US Census Bureau partnership specialist and liaison to the Russian-speaking community. “We try to overcome it.”

During the previous census count 10 years ago many areas in South Brooklyn, including parts of Coney Island and Brighton Beach, were named hard-to-count. “The main reason was that the population there consists of many immigrants: Russian-speaking but also Spanish-speaking. Some fear the government, others don’t speak English,” said Savinkin.

Approximately two years ago the community organized the Complete Count Committee for Russian American New Yorkers which consists of 47 organizations serving various neighborhoods. Similar efforts occurred for the first time in 2000, although on much smaller scale.

“Our goal is to count everybody. We want 100 percent return rate,” said Gene Borsh, chair of the committee and a director of Local Russian Émigré Organizations (LOREO), a grass roots political action group supported by HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. “During those two years we worked to organize public events and seminars on the census in every possible place: on the streets, in community centers, medical facilities, stores, etc. For us this is one of the most important communal projects. Census not only counts people, it gives political power, influence, and funds”.

Community leaders have been using carefully chosen arguments to reassure undocumented immigrants. One is that if Congress passes immigration reform and the undocumented need a government document proving they were in the US at certain point in time, they can ask the Census Bureau to provide it (no one can withdraw personal data from the census except the person who filled out the questionnaire).

Activists have also reminded immigrants that their information is strictly confidential and that, whether they are in-status or not, they all use the area’s schools, roads, and hospitals and for that federal funds – distributed on the basis of census figures – are needed.

The results of these efforts combined with census and Russian-language media outreach may already be visible. “The same areas in South Brooklyn that in 2000 were among the worst in the city, this time, at least as of now, are ahead of many others,” said Savinkin. “For example one census tract in Coney Island where the final score in the count 10 years ago was between 53-59%, this time only 2 weeks after the counting efforts started already had the response level of 42%.”

Still, problems persist and not everyone is convinced. In some cases arguments only work halfway. Vera, a 49-year old home attendant from Ukraine, who did not want her last name used, decided not to include her personal information on the form, such as her name and phone number. She offered only a brief explanation: “security reasons.”

Nevertheless, Vera said through a translator that she filled out the rest of the questionnaire because she wanted to be counted. She hopes that more funding will come to the area. “Maybe college fees won’t be raised,” she wondered. “My son is a student.”

Another challenge for the communal project has been uniting the efforts of various groups of Russian-Americans living in New York. The last wave of Russian- speaking immigrants came to the US in the 1980s and 1990s, bringing members of many diverse communities from Russian Jews to ethnic Russians and other groups from the former Soviet Union such as Armenians.

Regardless of their ethnicity, a significant number of the newcomers were in their 50s or older, and for many mastering English turned out to be a difficult task. According to the 2000 Census, out of approximately 243,000 New Yorkers who declared Russian ancestry more than 106,000 used a language other than English as the primary language in their home.

To ease the language barrier, for the first time this year Russian was introduced as an official census language, meaning that there are questionnaires available in Russian.

The other census languages are English, Spanish, Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean. But only forms in English and Spanish have been mailed to people in their homes. Forms in the other four languages must be requested from the Census Bureau.

Savinkin doubts the form in Russian will have much impact in this year’s count. “On the letter from the census there is one line in Russian informing that if people need assistance, they should call a certain number. It does not even say that they can request the questionnaire in Russian. Only if they call they may find out.”

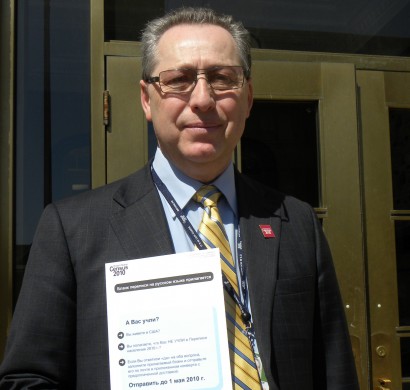

Census worker Igor Kazatsker helps Barno Akhundjanova, a 22-year old student, fill out the form. “This was my first time so I didn’t want to make a mistake,” she said. (Photo: Ewa Kern-Jedrychowska)

Igor Kazatsker, a census employee working at the site in the Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, says most of the people that he helped filled out the form in English, even though questionnaires in all official census languages were available at the site.

Another common issue Kazatsker has noticed is a need among immigrants to declair their ethnic identity. But on this year’s questionnaire only a very few ethnic groups are listed, which many immigrants find surprising, even discriminating. “Nevertheless, they insist to put Russian or Russian Jew in a blank space on the form. They are proud of their heritage,” he said.

The Feet in Two Worlds project on the Census is made possible thanks to the generous support of the 2010 Census Outreach Initiative Fund at The New York Community Trust and the Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund.