It’s almost noon. Even by Indian Standard Time, this is a little ridiculous. We had planned to leave at 10, yet the car is nowhere near packed. Dishes from breakfast are still piled in the sink, my sister and I are fretting over what clothes to bring, and my mother is wrapping pooris in aluminum foil and filling a giant sepia thermos with chai.

It is Christmas Eve day, and we are about to set off from our home in Los Angeles for Las Vegas, a trip we have made nearly every winter since I can remember. It is a bizarre family tradition, one that was particularly awkward for me to explain to my white American friends in middle and high school. What kind of parents take their three under-age children to Las Vegas every year for Christmas? The Indian kind.

The baseline chaos that normally prevails in my house is quickly deteriorating into a war zone. Dad: “Why aren’t you girls ready yet?! I told you to pack last night!” Mom: “Make sure you bring warm clothes! And a hairbrush! And a bathing suit!”

The phone rings. It is my “uncle,” one of my parents’ friends since their early years in Los Angeles, from “before you kids were even a twinkle in your mother’s eye.” He co-founded the Las Vegas tradition and brings his family every year as well. He is calling to see if we have left yet. Clearly, the answer is no. We tell him we are almost ready- a fib all parties tacitly and silently accept- and agree to meet in the parking lot of the Toys ‘R’ Us between our houses in one hour.

We scramble to finish packing, wash the dishes, and load up the car. Two and a half hours after our planned departure time, we pull out of the driveway. We meet up with two other families at Toys ‘R’ Us, have a quick cup of chai to energize ourselves for the drive, and get settled in our respective cars. My parents argue about the temperature—my mom is cold, my dad hot—we reminisce about Christmases past, disputing one another’s accounts, and listen to old Hindi songs—the ones I find melancholy and beautiful even when I don’t understand all the words. We also play word games; this is, after all, a perfect opportunity for vocabulary and spelling lessons.

After about three hours we stop to stretch our legs and picnic at a rest stop in Barstow, California, smack in the middle of nowhere. My mother pulls out the pooris and aloo subzi for which she is always responsible, one “Aunty” provides salad and condiments, and yet a third mom furnishes the paper plates and utensils. We dig in, even though our fingers are stiff from the cold and move more slowly than our hungry stomachs command. The chai, still steaming and apparently never-ending, warms our throats. Without a doubt, no other family at the rest stop is eating such an elaborate meal, but by now I’m past the point of comparing and blissfully take it all in.

We get back in our cars and resume the drive. This half is quieter, more peaceful. We nap, taking turns keeping my dad company while he drives. By the time we arrive in Las Vegas, the hotels and casinos have been alight for hours. We check in to the hotel, the kids eager to sleep, the adults ready to try their luck at the tables. And so begins our annual tradition.

~

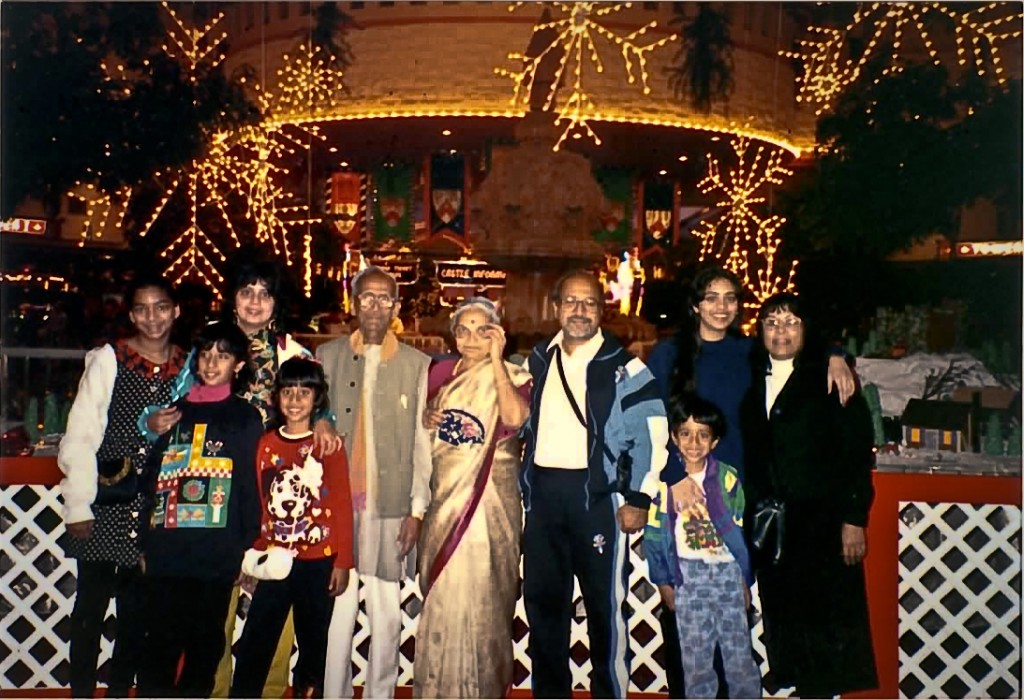

The author in Las Vegas, Christmas 1993. (Photo: courtesy of Nina Agrawal)

As a child, I hadn’t put much thought into the symbolism of this ritual—did it signify that my parents were godless capitalists?—but growing up I began to see it as one of the many anomalous experiences of my life as a first-generation American. My parents, who grew up in India, were not originally in the habit of celebrating Christmas. They weren’t Christian and they didn’t really know what the tree was for, or the jolly fat man in a red suit. They had a friend whose birthday fell on Christmas Day, their own wedding anniversary was a few days later, and they felt like taking off for an adventure. Thus the road trip to Las Vegas was born. It wasn’t about gambling or drinking—my mother to this day can’t finish a cocktail. It was about sharing the happiness in their lives and celebrating together.

When my parents and their friends had children, they incorporated us into their annual tradition. Nearly every winter between my sixth and sixteenth birthdays, we packed up the car and caravanned to Las Vegas with two, three, sometimes four other families. We usually stayed at the Excalibur hotel, where my sister and I pretended we were medieval princesses. During the day, we played carnival games and strolled through the giant hotel complexes. At night we ate out, saw a show, or watched movies in our room. There were no particular dinnertime traditions, except for the fact that the meal inevitably engendered chaos: one restaurant couldn’t seat 16 people, another had no high chairs; one menu didn’t have any vegetarian options, the other looked too bland. Somehow, in the end, we all were fed and content; this was a testament to nothing less than parental genius.

As the years passed, my sister, brother, and I amassed more stuffed animals than we could play with, grew bored of the hotels, and craved normalcy alongside our peers. At our insistence, my family began spending Christmas at home, opening presents under the tree on Christmas morning, singing carols, and cooking and sharing big meals.

Occasionally we still go to Las Vegas, but things have changed since the early days. Our parents no longer pack the toaster oven in anticipation of a wailing child hungry in the middle of the night. The “kids” don’t always come, and when they do, they play alongside the parents at black jack tables. Boyfriends, husbands, and even in-laws have joined the ranks. Cell phones now accomplish what elaborate signaling and honking used to on the road.

Last year, instead of going to Las Vegas, we drove up the coast to San Francisco. We had also made this journey many times as children, but on this occasion my sister’s new husband joined us, and it was just our family, as the Vegas cohort had long since disbanded.

We spent Christmas Eve and morning at home, passed the late morning in a frenzy getting ready, and in the afternoon headed up north. We stopped at sunset to eat near the water. There were no tables like at the rest stop in Barstow, nor were there any other families present to share our meal. We were freezing and the wind was blowing our plates off the benches. My brother sulked because he couldn’t find his camera.

Nothing felt quite right. Then my mom disappeared for a minute, digging in the trunk. She reappeared, smiling, holding the giant sepia thermos. We had all forgotten it. She poured out the piping hot chai to each of us; it comforted us the same way it always had. Our irritation evaporated with the steam and we settled into peace with one another.

This year we’re skipping Vegas again and heading to Joshua Tree. I can’t wait.

Nina Agrawal is a writer and editor based in Brooklyn, NY. She currently works on education reform at the Collaborative for Building After-School Systems, a national partnership dedicated to expanding high-quality after-school programs for children, and previously served as an editor at Americas Quarterly magazine.

Fi2W is supported by the New York Community Trust and the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation with additional support from the Ralph E. Odgen Foundation and the Sirus Fund.