This story was published in partnership with Yes! Magazine.

When Linda Sue Park was growing up in Illinois, she spent hours at her local library, devouring Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie series.

Park, 61, is a Newbery Medal-winning writer and the daughter of Korean immigrants. As a child, she imagined going on adventures with Wilder’s titular character, Laura. She indulged in daydreams of sitting by the fireplace with the Ingalls family, White homesteaders whose experiences are beloved by generations of American readers.

“I’ve spoken to many children of immigrants who really latched onto these books,” Park says. “I have this theory that we were searching so desperately for a road map on how to be American.”

As a Korean American kid growing up in Colorado in the 1990s, I, too, was a fan of the Little House series, and I was fascinated by the lore of the Old West. When my sixth-grade class visited an historic hotel in southern Colorado, a tour guide pointed at bullet holes dotting the ceiling—evidence, he said, of bandit-style brawls. I was hooked.

The characters who inhabited the Old West drew me in with their boisterous attitudes, wild independence, and refusal to conform to societal expectations. But in all of the stories I encountered, I never once came across Asian American people. I didn’t see them in history books, on tours, or on plaques.

It turns out they were there all along. I just didn’t know their stories.

Mia Warren at Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico, where Ancestral Puebloan peoples lived. Photo courtesy of Mia Warren.

At age 16, I read Killing Custer, by Native writer James Welch, who decimates the romanticized view of Gen. George Armstrong Custer. The book introduced me to a tradition of historians working to correct the myth of the whitewashed American West. In time, my imaginings of the Old West expanded to include the Black, Latinx, and Asian American people who lived here, too—and who, like Whites, were settling on lands taken from Indigenous people.

“Asian Americans lived in the West,” writes Professor Gail M. Nomura. “They shaped the western landscape through cultivation and toil. They were not just excluded. They were not just passive victims to be conquered and subjugated. They built and they molded and they struggled.”

Though their presence has been written out of the record, nearly 15,000 Chinese men built the Central Pacific line of the first transcontinental railroad, an estimated 150 to 2,000 workers dying in the process. But none of them were invited to pose for the iconic 1869 photo that documented the joining of East and West by rail.

Chinese people were present—and prolific—in the Old West. “In 1870, almost 30% of the Idaho Territory’s population were Chinese,” says Liping Zhu, 63, a professor of history at Eastern Washington University, in Cheney, Washington.

Chinese American communities faced great hostility and racial violence in the late 1800s. After the transcontinental railroad was completed, thousands of Chinese Americans moved to Truckee, California, in search of work. Within a few months, White townspeople set Chinatown on fire. A local Causasian League plotted to drive out all Chinese residents. In 1871, White residents of Los Angeles lynched 17 Chinese American men and boys. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred all Chinese laborers from immigrating to the U.S.

Zhu’s career spans several decades, uncovering the presence of Asian Americans in the Old West, shedding light on how they lived, and how their legacies have shaped our new understanding of an Asian American Old West. His scholarship challenges us to look past the stereotype that Chinese Americans were merely passive victims in the face of adversity. They also built lives for themselves.

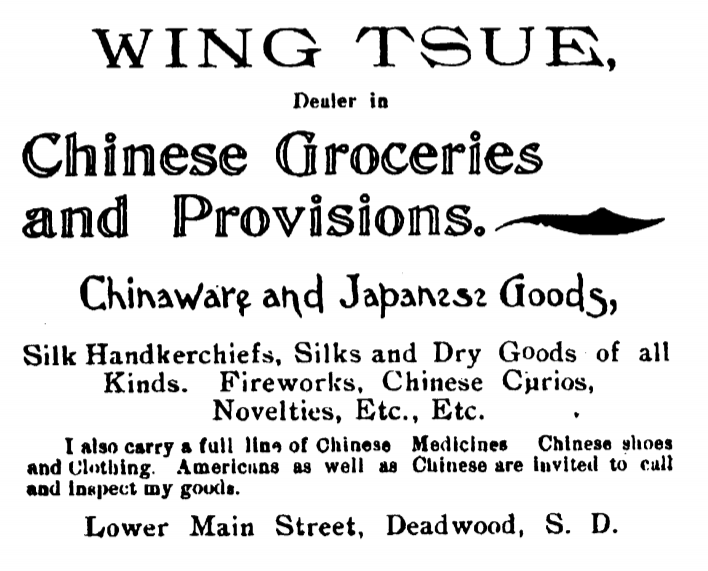

Advertisement in the Black Hills Residence and Business Directory, May 1898. Image from the Centennial Archives of the Deadwood Public Library.

His research has uncovered court documents showing how Chinese workers sued their employers for lost wages. Chinese Americans operated laundries in Western mining towns, allowing them to gain economic mobility: Their profits often exceeded a standard 19th century wage of $1.50 per day.

“Laundry men could make up to $10 a day,” says Zhu. “They were ‘mining the miners.’”

A 2008 study, which cites Zhu’s research, suggests the importance of Chinese businessmen in Deadwood, South Dakota. In 1800, the town of 5,000 was home to “two prominent merchants, Hi Kee and Fee Lee Wong,” who were “highly respected and well-known by the entire community.”

Archaeological excavations in Deadwood hint at thriving intercultural relationships between White customers and Chinese businesses, from restaurants and gaming halls to opium houses and practitioners of Chinese medicine. White Deadwoodians attended Chinese funerals and cultural celebrations. Chinese Deadwoodians attended Fourth of July picnics.

These encounters weren’t necessarily a mark of assimilation, Zhu says, choosing to use the term “cultural fusion” instead. Cultural practice sharing went both ways.

By 1900, the Chinese population of Deadwood had dwindled to less than 90 people. But Zhu still keeps in touch with their descendants. “I don’t call myself a revisionist historian,” he says. He studies history—history that’s always been there.

Linda Sue Park’s book Prairie Lotus (2020) chronicles a young Asian American girl’s life in Dakota Territory in the late 1800s. Courtesy of Clarion Books.

Linda Sue Park didn’t set out to write a book about Asian Americans in the Old West. But more than 50 years after she first picked up the Little House series, she published Prairie Lotus: a middle-grade story about an Asian American girl growing up in Dakota Territory in the late 1800s.

Hanna, the main character in Prairie Lotus, is the daughter of a woman who immigrated to the U.S. from China and a White American man. She arrives in the fictional town of La Forge with dreams of attending school and becoming a dressmaker.

Things aren’t easy for Hanna. She endures constant racism and xenophobia, experiences drawn from Park’s own life. But Hanna’s life isn’t just about the racism she endures. Some of my favorite passages dive into her passion for garment-making.

“I wanted to give a little bit of a twist to the Asian laundry. I wanted to take that stereotype and work with it, but at the same time subvert it,” says Park, who comes from a family of accomplished needlewomen.

In a particularly multilayered twist, we learn that Hanna’s late mother—born in China and brought to the United States by Christian missionaries—was half Chinese and half Korean. It was Park’s way of writing Koreanness into the story long before substantial numbers of Koreans immigrated to the U.S.

Park thought a great deal about how to incorporate Native characters into the story, and she places Hanna in the context of a land that was stolen from Indigenous Ihanktonwan people. In the first few pages of the book, Hanna encounters Ihanktonwan women. These scenes were Park’s attempts in imagining what encounters with Indigenous people might have been like for a young girl on the American frontier.

In the wake of the Atlanta shootings, after a year of heightened anti-Asian racial violence, Park has noticed a renewed interest in her books.

“Asian hate is not new. It’s been around for a long time. We’re just talking about it now,” she says. Park says she wants Prairie Lotus to be a resource for young readers about Asian American history—the good and the bad.

Park’s first book, Seesaw Girl, was published in 1999. 22 years later, she’s published 28 books, created a community for Korean American authors and is an active member of the nonprofit We Need Diverse Books. But she looks forward to the days when even more Asian American writers publish stories about Asian Americans in the Old West and beyond.

“There’s a lot more space for these stories, but I get so impatient. I don’t want three books. I want 300 and I want them now.” To Asian American authors, she says, “Please hurry up.”

Fi2W is supported by The Ford Foundation, the David and Katherine Moore Family Foundation, the Ralph E. Ogden Foundation, the Listening Post Collective, an anonymous donor and readers like you.